notes on Oklahoma!

my year of Rodgers & [relax]Hammerstein[ation]

Back in Summer 2019 on a total whim I caught a touring performance of Oklahoma! at the Benedum Center in Pittsburgh. My awareness of Oklahoma! was that it was a very popular musical called Oklahoma!, which in itself held absolutely no appeal for me whatsoever. But even seeing a touring performance from a mediocre seat with no context left me floored; I felt instantly like I’d seen one of the best works of art ever produced in this godforsaken country. Nonetheless, in the intervening years I’ve neglected to dive as deep on Rodgers & Hammerstein as I have, say, Stephen Sondheim, who even in spite of my “greatest of all artists” feelings I still I have some big oversights for1; there’s no doubt hearing Sondheim talk about Oscar Hammerstein has helped motivate my interest in learning more about the latter. So I’ve resolved to spend 2025 listening to, watching, and otherwise learning about every musical by Rodgers & Hammerstein, starting with a broad reappraisal of Oklahoma!, their first(!) collaboration.2

Oklahoma! emerged out of a confused web of circumstances among the New York theatre sphere of the 1920s, 30s and 40s. Composer Richard Rodgers was reaching the end of his decades-long collaboration with songwriter Lorenz Hart, whose alcoholism had placed a strain on their working relationship and, shortly after Oklahoma premiered, would result in his death at 48.3 Oscar Hammerstein II had his creative tendrils running in many directions: ongoing collaborations with Jerome Kern, with whom he wrote early career pinnacle Show Boat4; meetings regarding various ventures in Hollywood; and work on Carmen Jones, his modern reworking of the opera Carmen with a cast of African American performers. Rodgers and Hammerstein had been in each other’s orbits over the years but had not yet collaborated, in part because Rodgers’ valued his partnership with Hart and didn’t want to alienate the increasingly ailing songwriter. New York’s Theatre Guild, which helped germinate and co-produce numerous plays and musicals over the early decades of the 20th century, had been intensely pursuing both Rodgers and Hammerstein for an adaptation of Lynn Riggs’s play Green Grows the Lilacs5, which had premiered to some success in the early 30s. In addition to these creative cross-sections was the overall desire by all parties involved to elevate musical theatre beyond its stagnant, vaudevillian tendencies; it’s impossible to read about the aspirations of Rodgers and Hammerstein, as well as the Theatre Guild’s producers, without thinking about Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total artwork,” the epic work comprised of every art form. And when Oklahoma at last premiered, it seemed they had succeeded in their mission. Rodgers wrote:

I have long held a theory about musicals. When a show works perfectly, it’s because all the individual parts complement each other and fit together. No single element overshadows any other. In a great musical, the orchestrations sound the way the costumes look. That’s what made Oklahoma! work. All the components dovetailed. There was nothing extraneous or foreign, nothing that pushed itself into the spotlight yelling, “Look at me!” It was a work created by many that gave the impression of having been created by one.6

With Oklahoma, Rodgers & Hammerstein managed to produce such a work, and to do so with so many dualities: the high of the theatre with the low of the musical; universal themes, but in a hyper-specific cultural milieu; patriotic (a necessary characteristic given the era of its production), but ambiguous, even wry, needly, about the American project. And naturally layers of duality are contained within the work itself: the central conflict finds farm girl Laurie torn between thoughtful but irreverent cowboy Curly and gruff and familiar farmhand Jud; Laurie has a foil in Ado Annie, a friend who herself can’t decide between suitors and whose choices are made for her by her shotgun-toting patriarch; the rural environments of the musical are being gradually encroached upon by the threat of urbanism in Kansas City; Oklahoma is not yet a state, but a territory, inhabiting a space between national categories. All of these and more are embodied in the musical—and even within individual numbers, like “The Surrey with the Fringe on Top” or “People Will Say We’re in Love,” there is a magnetic push and pull between reality and fantasy, action and passivity, love and disdain. This all naturally coalesces in what is probably the musical’s greatest innovation, the Dream Ballet, wherein Laurey’s conflicts are allegorized in a fantasy dance number that set the stage for countless sequences like it all throughout musical theatre and film over the ensuing century.

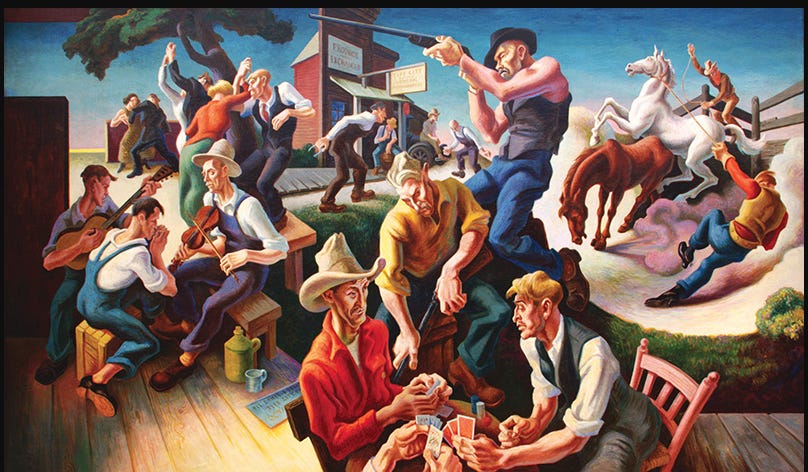

It’s hard to articulate just why Oklahoma feels to me, just as it did in 2019, like one of the Great American Works—it is in its many of these aforementioned pushes and pulls, in its innovations of the form that still feel fresh today, in the graceful and infectious turns of phrase and melody, in every song’s bittersweet, dreamy, and often funny gestures toward a better, different world. Tied to my initial exposure to the musical was a brief fixation I had on Regionalism, the Midwestern art movement from around the same period as the show that produced Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, who might just as well have been painting episodes from Riggs’ play and the musical adapted from it:

The muical was also only a few years removed from John Ford’s first totemic masterworks of the American West, Stagecoach and The Grapes of Wrath. Indeed, Ford and his muse John Wayne were early considerations for director and star of the Theatre Guild’s production of Riggs’ play.7

Oklahoma and many of these contemporaneous works age in fascinating and prickly ways, remaining metaphysically true in spite of their revisions and reappropriations of American iconography and how these symbols shift in meaning to the culture over the decades.

Notwithstanding the ways the unaltered text of the musical can remain relevant in the 21st century—insert “Curly has protagonist syndrome” or “Jud is an incel icon” or “Ado Annie should’ve just started a polycule” here—it was recently revived on Broadway with a show equally beloved and notorious for its subversions of the musical’s narrative, giving the enterprise a more foreboding, cynical tone, recontextualizing Jud’s villainy, and shifting the musical’s violent conclusion to comment upon American injustice, all without significantly altering the structure or Hammerstein’s libretto. Having listened to or watched four or five productions, it is a lovely and interesting reinterpretation of the material, though its academic engagement with the material tracks with it originating as an experiment in university theatre and it does give it a bit of a redundant postmodern flavor. Presumably it works significantly better in person on stage—NYC supremacy does sometimes (ironically in this case) win out…

My personal favorite production to listen to has proved to be the 1998 West End revival starring Hugh Jackman…it just feels like it has the richest vocal performances, toeing the line well between the show’s optimism and underlying menace. The 1955 film adaptation is…not good. It has a smart combination of ravishing images shot in actual rural landscapes and painterly, impressionistic soundstages, and it stages some of the numbers beautifully (in particular the Dream Ballet, “Kansas City,” and “The Farmer and the Cowman”). All of this having been said, much of the film is made up of sequences of characters standing stock still and singing in long master shots; not the most engaging or inventive rendition of the material. But all in all, it’s not a total loss; it’s meaningful that it immortalizes Agnes de Mille’s choreography for the stage production; De Mille was brought in on the original production in large part due to her choreography for Aaron Copland’s ballet Rodeo a year or two prior. Her understanding and melding of frontier physicality with ballet is truly singular and beautiful, just another of the many rich dualities on display in the show. The film also deserves some props for containing images like this:

I will likely have more to say about Oklahoma as the year goes on and I experience more of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s first few works, like Carousel and the film State Fair, which will both be for the first time. So for now, take much of this as stage-setting, as preamble, for a hopefully rewarding dive into arguably the most canonical artists of American musical theatre.

Likely to write about this someday but:

Sondheims I’ve listened to or seen, ranked:

Into the Woods

Sunday in the Park with George

Company

Sweeney Todd

Gypsy

Merrily We Roll Along

Anyone Can Whistle

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

Still have to see / listen to Evening Primrose, Follies, A Little Night Music, The Frogs (?? never heard of this lol), Pacific Overtures, Assassins, Passion, Road Show, and Here We Are. Not counting West Side Story or Do I Hear a Waltz here, because Sondheim only wrote the lyrics; West Side Story would probably be number one if I counted it here, and Do I Hear a Waltz is pretty underrated. Very fun.

Much of what I note here I gleaned from Tim Carter’s book Oklahoma! The Making of An American Musical, a very thorough account of the musical’s origins and production that probably has more detail than anyone but the biggest nerd would care about but does have some amazing information and quotes. I should also note that I am not a music guy…I love music, and I love musicals, but I cannot understand or articulate exactly what is good or bad about music in the same way I might be able to about movies or video games or Survivor or human and social services lol. So please bear with and/or enjoy the ride with me through this learning experience.

Beautiful serendipity that I embarked on this Rodgers & Hammerstein quest the same year as Richard Linklater’s film Blue Moon, about Lorenz Hart (Ethan Hawke) on the night of Oklahoma’s premiere.

There are some grouchy arguments that Show Boat was just as much the revolutionary shift in musical theatre that Oklahoma was and doesn’t get enough credit; due to this discourse, I made listening to multiple productions of Show Boat, and watching the 1936 film, part of this project. It’s a lovely musical with tremendous numbers, but it is, ultimately, a baby step toward the innovations of Oklahoma; it remains bogged down in the vaudeville and burlesque cliches that musical theatre overcame in the wake of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s partnership, and though it does ostensibly tell a story about a marginal, middle American milieu, its subject is, nonetheless, people becoming famous actors. That’s not inherently bad, but part of what’s so special about Oklahoma is that it fully abandons the world of the theatre in subject while keeping showmanship and storytelling and performance as central aspects of its structure and form. Show Boat isn’t quite there. But it is very good! I do highly recommend it!

Because I have nowhere better to place it, an amazing snippet from Lynn Riggs on the Oklahoma he remembers but felt unable to articulate in his work as a playwright:

"I can’t make—in drama or poetry—the quality of a night of storm, for instance, in Oklahoma, with a frightened farmer and his family fleeing across a muddy yard (chips there, pieces of iron, horseshoes, chicken feathers)—to the cellar, where a fat bull snake coils among the jars of peaches and plums.

I can’t begin to say what it is in the woods of Dog Creek that makes every tree alive, haunted, fretful. I can’t tell you what dreadful thing happened last Christmas—when a son and his wife stumbled drunkenly into his mother’s house; the words that came out of brazen tortured throats, the murderous hints, threats—and all the time a little sick child, radiant, great-eyed, sat up in her bed and saw and heard and wept at something foul in her presence for the first time, life with venoms beyond her comprehension. And most of all—after sorrow, fear, hate, love—I can’t even begin to suggest something in Oklahoma I shall never be free of: that heavy unbroken, unyielding crusted day—morning bound to night—like a stretched tympanum overhead, under which one hungers dully, is lonely, weakly rebellious, and can think only clearly about the grave, and the slope to the grave."

Also beautifully and accidentally articulating what makes cinema so appealing

And Lee Strasberg, eventual teacher of method acting, appeared in the original production.